Some of the most powerful approaches in sociology are those that analyse the interactions of individuals. These are often seen as in opposition to more abstract views of social structure. I want to argue that this is not the case and that the two approaches are complementary and imply each other. I will develop this argument in this post and will take the argument further in a later post.

Interaction is the result of ongoing mutual constructions of the situation and of the attitudes and actions of its participants. Each participant constructs a representation and account and so negotiates a shared understanding that is sufficient to justify their actions as appropriate and so to ensure that the actions of the participants mesh or coordinate. Participants mutually - simultaneously and interdependently, but always imperfectly - legitimate their own actions and shape the actions of others by attempting to define limits to the options open to them. Each participant holds to an understanding of what he or she believes to be the case and what they believe others to believe. Thomas Scheff has seen this as the basis of consensus. Interactionists stress that such a consensus and meshing of actions is a contingent accomplishment: there may always be failures of understanding and mutual ignorance, leading to deviance, conflict, and a lack of coordination.

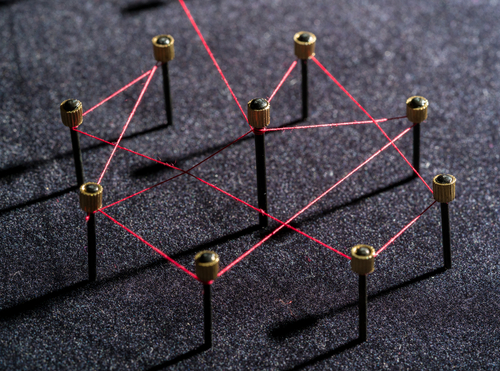

Through this process, individuals create a network of interactions among individuals. These individuals contribute to the production of what Goffman called an interaction order. This network of interactions, both face-to-face and mediated, may stretch across the whole population of a territory and beyond. My argument is that in producing this interaction order the individuals also contribute to the production of the social relations that comprise the 'macro' structure of their society. Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson showed long ago that these relations are the unintended and often unacknowledged results of the intentional acts of individuals.

For example, entering a shop to purchase groceries or clothing contributes to the reproduction of the relations of consumption and production: market relations, property relations, employment relations, monetary and credit relations, and so on. Similarly, making tax payments, drawing benefits, and engaging with polling station staff to cast a vote contribute to the production of political relations of governance: relations of citizenship, enforceable rights, relations of political representation, and so on.

Thus, we may identify property, employment, and monetary relations and also see these, in their combination, defining class relations. We may identify relations of schooling and examination, relations of parenting and socialisation, etc. And we may see all of these as involved in the movement of the individuals from one occupation to another and so as comprising , in their combination, relations of social mobility. We can study the mobility structures through the statistical associations among occupational categories, as the statistical rates that are the externally measurable reflection of the 'social facts' of occupational structure and social mobility. The structures of relations are real but not substantive. It is in this sense that Karl Mannheim in his 1932 essay 'Towards a Sociology of the Mind' said that 'capitalism' can be seen as 'a system of patterns which govern the relevant actions of the individual' and which 'exists only in a fluid state of interlocking actions'.

Thus, the outcome of interaction is a social structure of 'macro' relations that exist virtually within (that are 'underlying') the interaction order. This is the relational structure of a society, a structure of institutions and other 'structural parts' that underpin individual actions. It was, again, Mannheim who said that 'The problems and alternatives which the single individual faces in his actions are presented to him in a given social framework. It is this framework which structures the role of the person and in which his actions and expressions take on a new sense'.

In my next post I will look further at the nature of social structure.

Originally Posted July 30 2017.