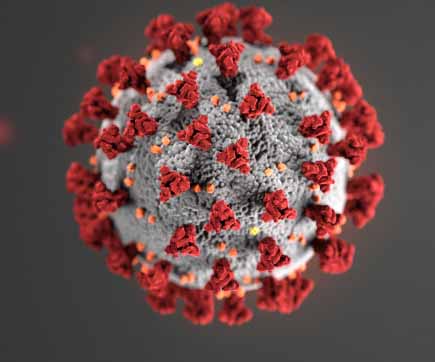

Covid-19, the Coronavirus, has rightly concerned us all, and governments worldwide have been forced to listen to the medical and scientific experts. What has not been recognised, however, is how much of the argument depends on sociological ideas, and on ideas from social network analysis in particular.

Researchers on social networks have shown how information, resources—and viruses—are communicated from one person to another through social networks, following the pattern of social relationships. James Coleman’s study of the diffusion of medical information, for example, showed that when tetracycline was introduced, information spread most effectively through the ‘central’ members of a network who were the influential brokers and opinion leaders. Studies of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases were shown by Tony Coxon to be explicable in terms of the density of connections in sexual relations and the patterns of centrality among actors.

A particularly influential argument in social network analysis has been Mark Granovetter’s view on ‘the strength of weak ties’. Granovetter showed that information flows readily and easily within dense and well-connected clusters within a network. It flowed round and round through the central members, and each individual member was likely to be the focal point of numerous paths of connection. The flow of information from one cluster to another, however, depended upon the relatively marginal people who had weak links to two or more clusters. Once such individuals communicated the information from the first cluster to a second, it could rapidly spread around the second cluster and then, in a chain reaction, spread further through its weak members.

This gives some insight into the spread of the coronavirus in China and Italy. In both cases, there was a definite geographical origin of the virus and a rapid spread around the region. Governments then attempted to close the boundaries of the region to limit the spread. As a result, the virus spread rapidly and widely within the regions. Such closure is far from perfect, even in China, and those who had no strong ties to the region and left it for home were able to spread the virus to other areas.

Policy across Europe and the US has been to delay the spread of the virus by managing social contacts. Faced with relatively diffuse points of origin, each country could avoid creating closed clusters and attempt to limit social contacts across the board with the intention of avoiding an exponential rise in the scale of infection. By flattening the curve of infection, the number of deaths might be minimised and also spread more evenly over a slightly longer period. As a result, there would be less pressure on the health services and correspondingly better treatment for those who fall ill.

An interesting illustration of this has been produced by the Washington Post in the link below. The article simulates various policies and shows that ‘social distancing’ and closure of public events can significantly reduce infection rates. The question is, of course, ‘will it work?’. The sociological theory suggests that it will, but medical knowledge about the virus is so limited that it is far from certain.

You can find the Washington Post simulation here (opens in a new window). Just click on 'Free access' and agree to the conditions.

< Risk and Moral Panic: A Sociological View of Covid-19 Power as a mode of control >